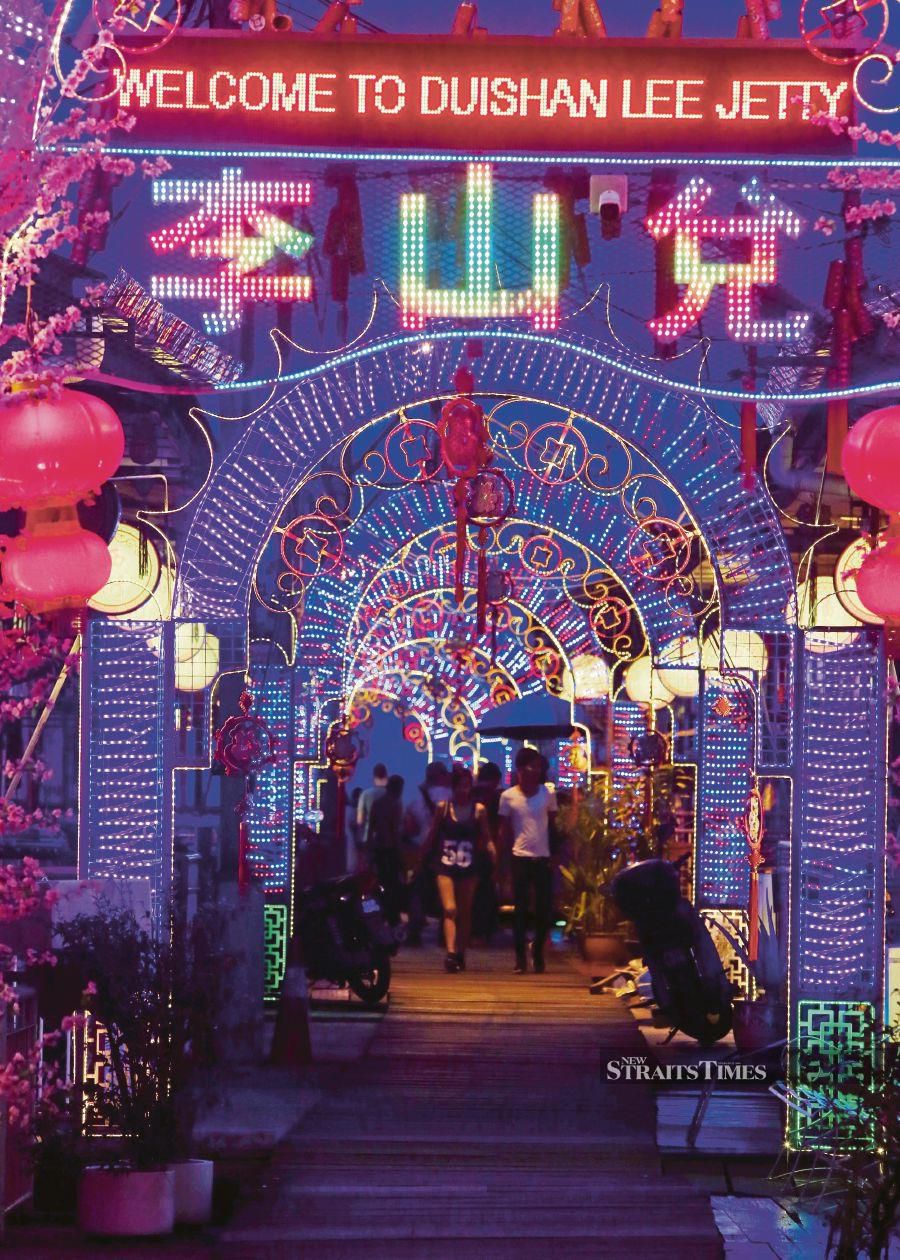

The decorated entrance to Lee Jetty in Pengkalan Weld. Some activists are concerned the jetties are becoming ‘theme parks’. -NSTP/Danial Saad

Conservationists are split over whether the Unesco World Heritage status accorded to parts of the city, which led to an influx of tourists, has done more harm than good to the clan jetties here.

The difference of opinion appears to rest on the best way to preserve the integrity of the jetties, with some calling for a ban on businesses operating on the jetties, while others feel there is a need to encourage it.

Universiti Sains Malaysia School of Housing, Building and Planning Professor Dr. A. Ghafar Ahmad says so long as there are residents staying on the jetties, they will be preserved.

“You must understand the history of the clan jetties, which began as a homestead for Chinese immigrants who came here for work in the then booming Penang maritime trade.

“So the true meaning of the jetties and its Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) is still intact as long as there are residents living there,” he tells the New Sunday Times.

However, he says, the jetties, especially Chew Jetty, may end up losing its OVU if the entire jetty is converted into a fully-commercial enterprise.

“It is all right for residents living there to carry out business or trade. You cannot stop that. In fact, residents should be encouraged to participate in economic activities as seen in other World Heritage listed sites.”

However, Ghafar qualifies this by stating that only residents living in the jetties should be allowed to conduct businesses to ensure they would invest in maintaining the place, which is also their home.

“They know the place, so they will take better care of it.”

He says there should be control over the types of businesses allowed to operate on the jetties as well as their opening hours.

“There should be do’s and don’ts for business operators as well as tourists visiting the jetties.

“There should be stringent rules, strictly enforced.

“The authorities must conduct research to determine these factors before implementing them.”

He says the authorities must look into limiting the number of tourists visiting the jetties.

This, he says, was to ensure that the narrow wooden boardwalks would not be damaged and that residents would not be inconvenienced with the presence of tourists at all times.

“The authorities can charge tourists a fee, which can be channelled towards maintaining the jetties.”

Ghafar says effort must be undertaken to improve the infrastructure of the jetties.

“For example, the toilets must be improved, instead of allowing residents to release their sewage into the sea. There should also be steps taken to protect the structure against fires.”

Conservation architect Tan Yeow Wooi disagrees with Ghafar on the way the jetties are being preserved for future generations.

He says the identity of the clan jetties is becoming lost due to the increasing number of tourists and commercial enterprises on the jetties.

“Looking back in history, we understand that these clan jetties were set up to replicate the immigrants’ hometowns in China, where the village residents mostly share the same ancestors.

“Of course, their homes in China would have been on land, but since they came to Penang to work as coolies at the docks or in the town, as well as sampan operators ferrying passengers and food in the straits channel, they may have decided to stick close to the sea.”

He says another clue that indicates the villages are built to mirror the residents’ hometowns is the fact that the temples in all the villages share the same name as the temple back in their ancestral villages in China.

“How can we claim that the clan jetties have retained their integrity if the residents of the clan surname begin leaving the jetties? It will no longer be a clan jetty.”

He says after the end of Penang’s free-port status, many residents moved out of the jetties in search of jobs.

“Due to social changes, only old people and young children are left in the jetties.

“However, with the tourism boom, most residents are now no longer living in the jetties, but are instead subletting the premises.”

He says physical changes to the facade of the jetties have compromised their character.

“It used to be wooden houses with thatched roof, but now you have more modern materials, such as stainless steel, glass and zinc.

“The facade (of houses) has also been removed to accommodate the trinkets being sold.”

Tan points out two different pictures of the same spot in Chew Jetty taken 10 years apart.

“Look at this picture. In the older picture, there is a mother cutting her son’s hair on the porch. In the newer picture, the entire area is filled with souvenirs.

“This is a shocking change and you will not be able to tell that it’s the same place.”

He says many had been caught by surprise when, two years ago, the businesses on the jetties suddenly increased by nearly 80 per cent within six months.

“In the beginning, residents used to complain that they were not getting any benefits from tourists. A few then started to do business selling souvenirs. Before you knew it, more shops began popping up.”

What is worse, Tan says, is the fact that most shops sell things that have nothing to do with the identity of the jetties.

“They sell things that are not related to the jetties and you can see more and more businesses catering to tourists and that’s really intrusive.”

He says the lack of control on the number of businesses operating in jetties shows that George Town World Heritage Inc is not managing the jetties well.

He says immediate action is needed before the settlements fully become markets.

“They need to control the commercialisation and gentrification to protect the OUV.”

~News courtesy of New Straits Times~

No comments:

Post a Comment